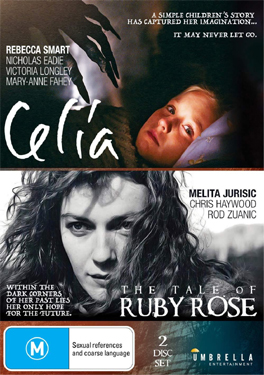

CELIA

(1989)/THE TALE OF RUBY ROSE (1987)

CELIA

(1989)/THE TALE OF RUBY ROSE (1987)Director(s): Ann Turner/Roger Scholes

Umbrella Entertainment

CELIA

(1989)/THE TALE OF RUBY ROSE (1987)

CELIA

(1989)/THE TALE OF RUBY ROSE (1987)Umbrella Entertainment double bills two supernatural-tinged stories of childhood trauma with their DVD set of CELIA and THE TALE OF RUBY ROSE.

CELIA: All nine year old Celia Carmichael (Rebecca Smart, THE COCA-COLA KID) wants for her birthday is a rabbit, but her father Ray (Nicholas Eadie, RETURN TO SNOWY RIVER) regards them as vermin (as does the Victoria government since the countryside is being overrun with wild rabbits that are eating crops). When her grandmother suddenly dies in her sleep, Celia thinks the Hobyahs – monsters from a school storybook – are responsible rather than old age (especially since Celia still sees her apparition in the nearby quarry). Celia is disappointed when she gets a bicycle rather than a rabbit for her birthday; however, new neighbors have moved in next door, and the mother Alice Tanner (Victoria Longley, THE MORE THINGS CHANGE…) looks like a younger version of her grandmother. The neighboring families get on well, particularly since the father Karl (Adrian Mitchell, MARAT/SADE) is one of Ray’s co-workers, Ray is attracted to Alice, and the Tanner kids form a gang with Celia to fight against her bullying cousin Stephanie (Amelia Frid), daughter of Ray’s army buddy John (William Zappa, THE ROAD WARRIOR), now a local police lieutenant. When Ray discovers that Alice and Karl belong to the communist group Australian Peace Council, he buys Celia a rabbit on the condition that she does not play with the Tanner kids. Celia initially keeps the promise, but the Tanner children come to her defense when Stephanie – jealous of Celia’s pet rabbit since her policeman father has sent hers to the zoo (in anticipation of the ban on pet rabbits) – and her friends attack her. When Karl loses his job, Celia blames Uncle John instead of her father (with whom she has a believable love-hate relationship) when the Tanners have to move away, and then she becomes convinced that he is one of the Hobyahs when he forcibly takes her rabbit away.

Although

CELIA's American video cover appended "Child of Terror" to the subtitle,

the film keeps good company with the psychological horrors of turbulent life

seen through an imaginative child’s eyes such as CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE,

PAPERHOUSE, THE REFLECTING SKIN, and PAN’S LABYRINTH. The climax’s

melding of reality with a monochrome Mike Mayfield crime film surely must also

have influenced the Orson Welles/THE THIRD MAN sequence in Peter Jackson’s

HEAVENLY CREATURES. While not a horror film in conventional terms, CELIA is

also not a children’s film by any stretch of the imagination. The Hobyahs

– the text of the story comes from James H. Fassett’s “Animal

Folk Tales” but the creatures have appeared in other folklore collections

– are glimpsed when Celia visualizes a passage of the story looking almost

rat or rabbit-like hopping on two feet, but the briefer glimpses we get of it

through Celia’s eyes in waking life are effectively jolting. The ending

is not so much horrific as tragic in a “loss of innocence” sense

through the attempt to keep children ignorant: Celia is told by her parents

and in church that communists are “bad people” who brainwash and

trick innocents, but she is unable to reconcile that with her beloved “free

spirit” grandmother who kept a “Handbook of Marxism” among

the many progressive books in her now-shuttered up bedroom; so is she to be

blamed for interpreting another character who seems to be more evil as a literal

monster? The film does not endorse its final act, yet one can kind of see Celia

coming away from it stronger even if she does (or will later) comprehend it

as bad.

Although

CELIA's American video cover appended "Child of Terror" to the subtitle,

the film keeps good company with the psychological horrors of turbulent life

seen through an imaginative child’s eyes such as CURSE OF THE CAT PEOPLE,

PAPERHOUSE, THE REFLECTING SKIN, and PAN’S LABYRINTH. The climax’s

melding of reality with a monochrome Mike Mayfield crime film surely must also

have influenced the Orson Welles/THE THIRD MAN sequence in Peter Jackson’s

HEAVENLY CREATURES. While not a horror film in conventional terms, CELIA is

also not a children’s film by any stretch of the imagination. The Hobyahs

– the text of the story comes from James H. Fassett’s “Animal

Folk Tales” but the creatures have appeared in other folklore collections

– are glimpsed when Celia visualizes a passage of the story looking almost

rat or rabbit-like hopping on two feet, but the briefer glimpses we get of it

through Celia’s eyes in waking life are effectively jolting. The ending

is not so much horrific as tragic in a “loss of innocence” sense

through the attempt to keep children ignorant: Celia is told by her parents

and in church that communists are “bad people” who brainwash and

trick innocents, but she is unable to reconcile that with her beloved “free

spirit” grandmother who kept a “Handbook of Marxism” among

the many progressive books in her now-shuttered up bedroom; so is she to be

blamed for interpreting another character who seems to be more evil as a literal

monster? The film does not endorse its final act, yet one can kind of see Celia

coming away from it stronger even if she does (or will later) comprehend it

as bad.

Smart gives a forceful performance for a child actor, and she is well-supported by Eadie, Longley (who died young in 2010) – who won an Australian Film Institute best supporting actress award – as well as television writer Mary-Anne Fahey as Celia’s mother (she was also nominated for the same award as Longley), and Clair Couttie as Celia’s friend Heather (whose quickly regrets how her jealousy of Celia’s new friendship with the Tanners has set some of the animosity with Stephanie in motion). The synthesizer score of Chris Neal (JACK BE NIMBLE) is comparable to Hans Zimmer’s and Stanley Myer’s work on PAPERHOUSE if not as operatic, but it surprisingly does not jar with the period setting. Cinematographer Geoffrey Simpson – who would later shoot SHINE, UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN, and OSCAR AND LUCINDA among other higher-profile films – captures Australia in the warm tones we’re used to seeing while Celia’s nightmares are captured in cool blues that seem alien against the rest of the film. Writer/director Ann Turner scripted the film years before its production. It won an award for best un-produced screenplay, and the film itself would win the Grand Prix at the Créteil International Women's Film Festival (it was also nominated at the Spanish Sitges fantasy film festival). Turner has only directed four other features to date including HAMMERS OVER THE ANVIL (1993) which Miramax picked a few years later in 2000 to exploit co-starring presence of Russell Crowe.

THE

TALE OF RUBY ROSE: In 1926, Henry Rose (Chris Haywood, ATTACK FORCE Z) and his

bride Ruby (Melita Jurisic, MAD MAX: FURY ROAD) moved into the Highlands of

Tasmania to snare wallaby and possum for the skin trade, eventually adopting

Gem (Rod Zuanic, FAST TALKING), a homeless boy as the substitute for the child

she miscarried. Seven years later, they live together in a mountain shack with

Henry putting all of their profits and his ambition into building a new barn.

Not having learned to read until she was twenty-one, Ruby has formed her own

ideas of how the world works based upon her intense childhood fear of the dark

which for her is a force that brings death and is to be fought off with light,

and informed by the various books that her estranged grandmother (Sheila Florance,

MAD MAX) sent to her illiterate father (Wilkie Collins, THE FRINGE DWELLERS).

Gem has grown tired of killing animals and has started setting them free, causing

Henry to believe that his work is being poached by Bennett (Martyn Sanderson,

AN ANGEL AT MY TABLE), the father of Ruby's intended suitor from years before.

Henry barely tolerates Ruby's fears but grows angry when she passes them onto

Gem. Troubled by childhood memories of her dark bedroom and something that happened

in there that she cannot remember, Ruby takes the opportunity while Henry and

Gem are away trapping to travel down into the valley on her own ostensibly to

sell off some of their cleaned skins but also to reconnect with her past. Along

the way, she encounters Bennett who has indeed been lurking in the area poaching

– but out of desperation rather than malice – who tells her that

her grandmother is now living with her father in town, and makes vague reference

to something that happened to her as a child. Ruby tries to care for him but

waking up next to his corpse only encourages her beliefs that death is coming

for her with the darkness. After taking a side trip to deliver Bennett's corpse

to his wife (Nell Dobson), she returns to her family home in hopes of facing

her past.

THE

TALE OF RUBY ROSE: In 1926, Henry Rose (Chris Haywood, ATTACK FORCE Z) and his

bride Ruby (Melita Jurisic, MAD MAX: FURY ROAD) moved into the Highlands of

Tasmania to snare wallaby and possum for the skin trade, eventually adopting

Gem (Rod Zuanic, FAST TALKING), a homeless boy as the substitute for the child

she miscarried. Seven years later, they live together in a mountain shack with

Henry putting all of their profits and his ambition into building a new barn.

Not having learned to read until she was twenty-one, Ruby has formed her own

ideas of how the world works based upon her intense childhood fear of the dark

which for her is a force that brings death and is to be fought off with light,

and informed by the various books that her estranged grandmother (Sheila Florance,

MAD MAX) sent to her illiterate father (Wilkie Collins, THE FRINGE DWELLERS).

Gem has grown tired of killing animals and has started setting them free, causing

Henry to believe that his work is being poached by Bennett (Martyn Sanderson,

AN ANGEL AT MY TABLE), the father of Ruby's intended suitor from years before.

Henry barely tolerates Ruby's fears but grows angry when she passes them onto

Gem. Troubled by childhood memories of her dark bedroom and something that happened

in there that she cannot remember, Ruby takes the opportunity while Henry and

Gem are away trapping to travel down into the valley on her own ostensibly to

sell off some of their cleaned skins but also to reconnect with her past. Along

the way, she encounters Bennett who has indeed been lurking in the area poaching

– but out of desperation rather than malice – who tells her that

her grandmother is now living with her father in town, and makes vague reference

to something that happened to her as a child. Ruby tries to care for him but

waking up next to his corpse only encourages her beliefs that death is coming

for her with the darkness. After taking a side trip to deliver Bennett's corpse

to his wife (Nell Dobson), she returns to her family home in hopes of facing

her past.

Like CELIA, THE TALE OF RUBY ROSE uses belief in the supernatural as a way of exploring the horrors of life as seen by a child. In the case of this film, however, Ruby is an adult whose understanding of the world has been shaped by trauma and stunted by the circumstances around her. Her mother's death and grandmother's estrangement from her life are seen as absences that place her in the care of men who are not insensitive or cruel but are ultimately ill-equipped to emotionally support her; with Henry driven to make life better for his family and at a loss as to how to deal with his wife's beliefs – although he taught her to read, his own education seems apparently limited or narrowly-focused – and frustrated when he cannot distract her with the necessities of daily living in a harsh environment. Ruby, in turn, both depends upon him and Gem but sees them not as willfully ignorant, rather has helpless and unsuspecting as the animals they snare to the darkness she fears. If the climactic revelation might seem laughable on paper, its repercussions for a child and adult without the faculties to put them in context is tragic. Although co-produced by Hemdale (minus David Hemmings) and Anthony I. Ginanne (TURKEY SHOOT), the film is as far from Ozploitation as CELIA and might be more likened to the New Zealand film VIGIL from Vincent Ward), but it is a rewarding viewing experience worthy of discovery. Apart from the TV movie CABLE, writer/director/editor Roger Scholes' other credits have been primarily television documentaries while the fantastic photography is the work of Steve Mason who moved up from the likes of Australian favorites like STRICTLY BALLROOM to Hollywood crap like the John Travolta thriller BASIC and the Miramax slasher VENOM.

Released

direct to video in 1990 by Trylon Home Video, CELIA was long in reaching DVD,

debuting in Australia from Umbrella in 2009 followed quickly by Second Run in

the UK while an American release did not come about until 2013 as part of Scorpion

Releasing's Katarina's Nightmare Theater line. All showcased the same anamorphic

widescreen transfer which has been utilized here in Umbrella's double feature

edition which is identical to the 2009 disc. The extras have been ported over

from the Australian Region 4 PAL DVD starting with a vintage “Sunday Show”

profile on the film (7:04). Turner emphasizes that CELIA is not a film for children,

and confirms that the film is criticizing the contemporary political longing

to take Australia back to the idyllic fifties (noting a growing social intolerance).

For weekend TV show coverage, it’s refreshingly substantive. Turner also

appears in a newer audio interview (10:57) by The Weekend Australia film columnist

David Stratton. She talks about the inspiration for the screenplay in an article

about the “Rabbit Muster” and the blacklisting of a friend’s

father during the fifties for being a communist. She also talks about the parallel

of the scapegoating the communists and the rabbits by politicians to address

different fears. Apparently no Australian trailer could be found – or

any English-language trailer for that matter (the film went direct-to-video

in the US from the short-lived Trylon Video) – so the Australian and American

discs offer a German trailer (1:35) titled CELIA: EINE WELT ZERBRICHT (“A

World Falls Apart”) that shockingly focuses on the drama rather than the

horror.

Released

direct to video in 1990 by Trylon Home Video, CELIA was long in reaching DVD,

debuting in Australia from Umbrella in 2009 followed quickly by Second Run in

the UK while an American release did not come about until 2013 as part of Scorpion

Releasing's Katarina's Nightmare Theater line. All showcased the same anamorphic

widescreen transfer which has been utilized here in Umbrella's double feature

edition which is identical to the 2009 disc. The extras have been ported over

from the Australian Region 4 PAL DVD starting with a vintage “Sunday Show”

profile on the film (7:04). Turner emphasizes that CELIA is not a film for children,

and confirms that the film is criticizing the contemporary political longing

to take Australia back to the idyllic fifties (noting a growing social intolerance).

For weekend TV show coverage, it’s refreshingly substantive. Turner also

appears in a newer audio interview (10:57) by The Weekend Australia film columnist

David Stratton. She talks about the inspiration for the screenplay in an article

about the “Rabbit Muster” and the blacklisting of a friend’s

father during the fifties for being a communist. She also talks about the parallel

of the scapegoating the communists and the rabbits by politicians to address

different fears. Apparently no Australian trailer could be found – or

any English-language trailer for that matter (the film went direct-to-video

in the US from the short-lived Trylon Video) – so the Australian and American

discs offer a German trailer (1:35) titled CELIA: EINE WELT ZERBRICHT (“A

World Falls Apart”) that shockingly focuses on the drama rather than the

horror.

Although given a theatrical release in the UK by Hemdale, THE TALE OF RUBY ROSE went straight to video stateside from their short-lived home video arm (the rights to the film are with MGM now). The film makes its DVD debut courtesy of Umbrella whose anamorphic 1.85:1 widescreen transfer is sourced from materials provided by the National Film and Sound Archive and restored in association with Screen Tasmania. Although the audience for such a film is limited, it is too bad that Umbrella did not do a Blu-ray because the restoration is gorgeous while the Dolby Digital 5.1 encoding of the Dolby Stereo track is conservative and supportive. There are no menus or extras. (Eric Cotenas)