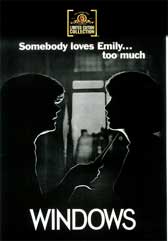

WINDOWS

(1980)

WINDOWS

(1980)Director: Gordon Willis

MGM Limited Edition Collection

WINDOWS

(1980)

WINDOWS

(1980)Never released on home video and rarely seen after its theatrical release, THE GODFATHER cinematographer Gordon Willis’ sole directorial effort WINDOWS makes its digital bow courtesy of MGM’s manufactured-on-demand DVD program.

Recently separated but still working in close confines with her husband (Russell Horton, ANNIE HALL), Emily (Talia Shire, THE GODFATHER) is viciously assaulted in her apartment one night after work by a switchblade-wielding pervert. The trauma brings back her childhood stuttering problem and she is unable to even describe what little she remembers of the attack to investigating officer Luffrano (Joseph Cortese, EVILSPEAK). Unable to remain in her old Brownstone apartment, she quickly picks up and moves across the Brooklyn Bridge to an apartment building. Unfortunately, this doesn’t sit well with her former neighbor Andrea (Elizabeth Ashley, the sinister nurse of COMA) with whom she also shares an almost-negligently disinterested shrink (Michael Lipton, NETWORK) who proves ineffective in addressing Emily’s issues and Andrea’s tendency towards obsessive attachments. Soon enough, Andrea has taken a loft on the river and is spying on poor Emily with a massive phallic telescope, and she violently disapproves of the budding relationship between Emily and Luffrano.

Photographed

and directed by two-time Academy Award-nominated – for ZELIG and THE GODFATHER,

PART III – cinematographer Gordon Willis, WINDOWS is either a psychological

drama with emphasis on the wrong character or a thriller that shoots itself

in the foot early on. Had it been a psychological drama following Andrea’s

psychological problems and her obsession with cypher Emily, then it might not

have mattered it is entirely obvious from her very first scene that Andrea is

wacko. Since it is revealed extremely early on that Andrea has set up Emily’s

assault at the hands of a sketchy cab driver (Rick Petrucelli) – I’m

sorry, it’s not a spoiler, look at the poster image, any synopsis of the

film (including the single sentence on the back of MGM’s cover), and you

know the film isn’t about an unknown stalker terrorizing the heroine but

specifically a woman terrorizing another woman (the film’s TV spot seems

to be the only advertising that tries to suggest it’s a woman stalked

by madman scenario) – and we see that Andrea is behind every unnerving

thing that happens to Emily along the way, there is more suspense coming from

wondering how the script will contrive to create clues for Luffrano to suspect

Andrea than from how long it will take Emily to wise up about her friend’s

strange behavior. The scenario – such as it is in Barry Siegel’s

sole writing credit – would perhaps have worked more effectively as a

piece of 1970s or 1980s Italian softcore erotica (or perhaps a 1990s Skinemax

offering).

Photographed

and directed by two-time Academy Award-nominated – for ZELIG and THE GODFATHER,

PART III – cinematographer Gordon Willis, WINDOWS is either a psychological

drama with emphasis on the wrong character or a thriller that shoots itself

in the foot early on. Had it been a psychological drama following Andrea’s

psychological problems and her obsession with cypher Emily, then it might not

have mattered it is entirely obvious from her very first scene that Andrea is

wacko. Since it is revealed extremely early on that Andrea has set up Emily’s

assault at the hands of a sketchy cab driver (Rick Petrucelli) – I’m

sorry, it’s not a spoiler, look at the poster image, any synopsis of the

film (including the single sentence on the back of MGM’s cover), and you

know the film isn’t about an unknown stalker terrorizing the heroine but

specifically a woman terrorizing another woman (the film’s TV spot seems

to be the only advertising that tries to suggest it’s a woman stalked

by madman scenario) – and we see that Andrea is behind every unnerving

thing that happens to Emily along the way, there is more suspense coming from

wondering how the script will contrive to create clues for Luffrano to suspect

Andrea than from how long it will take Emily to wise up about her friend’s

strange behavior. The scenario – such as it is in Barry Siegel’s

sole writing credit – would perhaps have worked more effectively as a

piece of 1970s or 1980s Italian softcore erotica (or perhaps a 1990s Skinemax

offering).

Shire is supposed to be mousy here, but underplays her role so meekly and pathetically that it even seems as if Cortese’s detective is taking advantage by striking up a romantic relationship with the victim of a traumatic assault; that said, her character is uninteresting and her performance uneven. Ashley is pretty unsubtle from the start and not given a lot to work with in terms of character depth, but she really takes advantage of her scenes in the therapist’s office to eke out some sympathy by conveying the palpable emotional pain caused to herself by her obsession. She then goes effectively overboard for the climax, but manages to transcend chewing the scenery and become genuinely unnerving (until Emily spoils things). Veteran actress Kay Medford (A FACE IN THE CROWD) plays one of Emily’s concerned neighbors.

Before

Woody Allen forged his collaboration with cinematographer Carlo DiPalma (TERROR

CREATURES FROM THE GRAVE), Willis was his cinematographer of choice, having

photographed INTERIORS, MANHATTAN, STARDUST MEMORIES, A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S

SEX COMEDY, ZELIG and THE PURPLE ROSE OF CAIRO. From the Allen films, he brought

with him to the film production designer Mel Bourne (THE FISHER KING), art director

Les Bloom (TAXI DRIVER), costume designer Clifford Capone (AMITYVILLE 3-D),

and associate producer/production manager John Nicolella (THE FAN), as well

as, of course, Shire from THE GODFATHER films (Petrucelli had bit parts in THE

GODFATHER and ANNIE HALL and would later appear in PURPLE ROSE OF CAIRO). Willis’

own cinematography emphasizes neon signs and artwork in the night exteriors,

backlighting and rim-lighting in the shadowy interiors, and bathes the New York

daytime exteriors in a perpetual autumnal afternoon glow. Ennio Morricone (ONCE

UPON A TIME IN AMERICA) phones in a score that is slick but often buried in

the mix and adding nothing to the scenes it underlines (the soundtrack was never

issued on LP and only recently received a CD release courtesy of Quartet Records

in Spain).

Before

Woody Allen forged his collaboration with cinematographer Carlo DiPalma (TERROR

CREATURES FROM THE GRAVE), Willis was his cinematographer of choice, having

photographed INTERIORS, MANHATTAN, STARDUST MEMORIES, A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S

SEX COMEDY, ZELIG and THE PURPLE ROSE OF CAIRO. From the Allen films, he brought

with him to the film production designer Mel Bourne (THE FISHER KING), art director

Les Bloom (TAXI DRIVER), costume designer Clifford Capone (AMITYVILLE 3-D),

and associate producer/production manager John Nicolella (THE FAN), as well

as, of course, Shire from THE GODFATHER films (Petrucelli had bit parts in THE

GODFATHER and ANNIE HALL and would later appear in PURPLE ROSE OF CAIRO). Willis’

own cinematography emphasizes neon signs and artwork in the night exteriors,

backlighting and rim-lighting in the shadowy interiors, and bathes the New York

daytime exteriors in a perpetual autumnal afternoon glow. Ennio Morricone (ONCE

UPON A TIME IN AMERICA) phones in a score that is slick but often buried in

the mix and adding nothing to the scenes it underlines (the soundtrack was never

issued on LP and only recently received a CD release courtesy of Quartet Records

in Spain).

It might be said that slickness is a problem with this film, which manages to come across as more sleazy than if the same idea had been filmed on a lower budget with more exploitative nudity and bloodshed (Andrea’s smoking, lip-licking, groaning and grunting suggests that she’s doing something more out of frame than simply watching Emily through the telescope); if WINDOWS were a product of the grindhouse, then the whole “murderously possessive lesbian” aspect of the script would feel less retrograde than it does in a studio pic that thinks itself too classy to include insert close-ups of Shire’s (or a body double’s) torso – once again not conflating the viewer’s gaze with that of the victim’s assailant – and elides the violence, sexual or otherwise, through slow dissolves or cutting away as if there was any ambiguity to be created about the outcome of these sequences. Despite the politically incorrect obsessive lesbian depiction, one is more apt to draw comparisons to FATAL ATTRACTION – one almost wonders if Glenn Close (or director Adrian Lyne) had Elizabeth Ashley’s performance in mind – than BASIC INSTINCT or SINGLE WHITE FEMALE. The setup of WINDOWS itself may even have been inspired by “The Telephone” episode of Mario Bava’s BLACK SABBATH (minus either of the sting-in-the-tail endings of the American and Italian versions).

Willis

can light beautiful images, but he is not much of a director and shows little

affinity for the genre (in fact, he was nominated for “Worst Director”

for the film at the 1981 Razzies). A Brian De Palma would have kept an eye on

establishing rhyming images and forging relationships between people and objects

with the movement of the camera, while a John Carpenter – who had recently

directed the similarly-themed SOMEONE’S WATCHING ME for television –

would have made the viewer complicit in the voyeuristic stalking of the heroine.

The film’s POV shots – whether through the telescope or representing

Andrea’s eyes – are always clearly delineated from the camera’s

own gaze. Even another contemporary cinematographer/director Peter Hyams (BUSTING)

might have kept created a more visually interesting picture with the same low-key

lighting. Willis went back to working solely as a cinematographer after this

with the aforementioned 1980s Woody Allen pics, Herbert Ross’ PENNIES

FROM HEAVEN, BRIGHT LIGHTS BIG CITY, THE PICK-UP ARTIST, THE GODFATHER PART

III, and another flawed thriller: the Aaron Sorkin-scripted MALICE. WINDOWS

was the second producer credit for Mike Lobell who has also abandoned the genre

in favor of comedies like CHANCES ARE, THE FRESHMAN and STRIPTEASE.

Willis

can light beautiful images, but he is not much of a director and shows little

affinity for the genre (in fact, he was nominated for “Worst Director”

for the film at the 1981 Razzies). A Brian De Palma would have kept an eye on

establishing rhyming images and forging relationships between people and objects

with the movement of the camera, while a John Carpenter – who had recently

directed the similarly-themed SOMEONE’S WATCHING ME for television –

would have made the viewer complicit in the voyeuristic stalking of the heroine.

The film’s POV shots – whether through the telescope or representing

Andrea’s eyes – are always clearly delineated from the camera’s

own gaze. Even another contemporary cinematographer/director Peter Hyams (BUSTING)

might have kept created a more visually interesting picture with the same low-key

lighting. Willis went back to working solely as a cinematographer after this

with the aforementioned 1980s Woody Allen pics, Herbert Ross’ PENNIES

FROM HEAVEN, BRIGHT LIGHTS BIG CITY, THE PICK-UP ARTIST, THE GODFATHER PART

III, and another flawed thriller: the Aaron Sorkin-scripted MALICE. WINDOWS

was the second producer credit for Mike Lobell who has also abandoned the genre

in favor of comedies like CHANCES ARE, THE FRESHMAN and STRIPTEASE.

MGM’s

single-layer manufactured-on-demand DVD presents windows in a progressive, anamorphic

widescreen (1.85:1) transfer (the poster artwork states that it is in Panavision,

but it’s a spherical film and Panavision would later distinguish between

anamorphic movies “Filmed in Panavision” and flat movies “Filmed

with Panavision cameras and lenses”). The presentation starts without

a modern MGM logo (the stereo roaring one with the MGM website address beneath);

instead, it opens with a vintage Transamerica United Artists logo. The transfer

appears to be new with neon colors leaping off the screen during the opening

credits and well-defined blacks in the silhouetted and rimlit chiaroscuro setups;

however, the master has not undergone the type of clean-up one expects of MGM’s

HD restorations, and there are several intermittent passages of white speckling

(usually at the reel-changes). It still looks good, but not what one expects

of a studio title. The Dolby Digital 2.0 mono track fares better, capturing

the highs and lows of Ashley’s hysterics without distortion while also

clearly rendering Morricone’s score. MGM’s cover art reproduces

the original theatrical poster faithfully, only cropping away the credits list

at the bottom and reprinting this information on the back instead. As with other

MGM MOD discs, there is only a main menu screen and the film has been divided

up into chapters at ten minute intervals. Sadly, no trailer has been included.

(Eric

Cotenas)

MGM’s

single-layer manufactured-on-demand DVD presents windows in a progressive, anamorphic

widescreen (1.85:1) transfer (the poster artwork states that it is in Panavision,

but it’s a spherical film and Panavision would later distinguish between

anamorphic movies “Filmed in Panavision” and flat movies “Filmed

with Panavision cameras and lenses”). The presentation starts without

a modern MGM logo (the stereo roaring one with the MGM website address beneath);

instead, it opens with a vintage Transamerica United Artists logo. The transfer

appears to be new with neon colors leaping off the screen during the opening

credits and well-defined blacks in the silhouetted and rimlit chiaroscuro setups;

however, the master has not undergone the type of clean-up one expects of MGM’s

HD restorations, and there are several intermittent passages of white speckling

(usually at the reel-changes). It still looks good, but not what one expects

of a studio title. The Dolby Digital 2.0 mono track fares better, capturing

the highs and lows of Ashley’s hysterics without distortion while also

clearly rendering Morricone’s score. MGM’s cover art reproduces

the original theatrical poster faithfully, only cropping away the credits list

at the bottom and reprinting this information on the back instead. As with other

MGM MOD discs, there is only a main menu screen and the film has been divided

up into chapters at ten minute intervals. Sadly, no trailer has been included.

(Eric

Cotenas)